A non-review that’s about me, not Blake

I love William Blake. My first wedding, we had readings from Michael Moorcock and we sang Jerusalem. My Sikh father abstained, disliking any hint of Christianity, while my partner and I gently mocked him.

For many years (at least two!), my daughter’s favourite poem – until unfairly usurped by Edward Lear’s nonsense verses – was Tyger, Tyger; and I miss those days, when our weekly Poetry Tea Time was the random verses I chose, a selection of dinosaur poems from my son, and a selection of Blake and Carroll from my daughter.

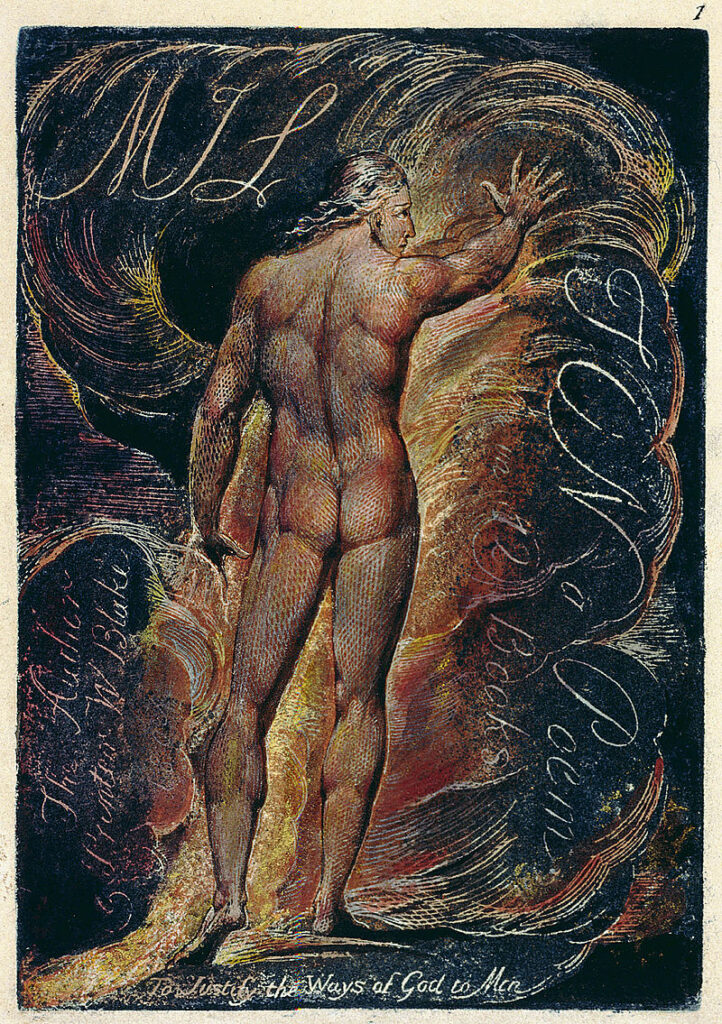

But, despite my love for William Blake, I have to confess I do not understand him. So I thought that the best way to try and understand him, at least a bit better, was to read Milton, again, out loud. To my children. It’s been interesting. Here are some of the things I learned.

The most important lesson is that I don’t need to understand Blake to enjoy his poetry. It’s not that surprising that a Malaysian atheist in the 21st century finds some of the ideas of a religious London mystic who died in almost 200 years ago.

Second, my kids had no better understanding of him than me, but the language is so vibrant, that they still responded to it, perhaps more as music than poetry. The underlying rebellion against authority probably helps too.

Third, it’s hard to reconcile the imagery of Blake’s London, with what we know of the globalism of the UK’s ambitions during this time. London seems like simultaneously the centre of the world and a small, dingy outpost of European civilisation.

But I think the most important lesson for me from re-reading Milton, twenty-odd years on from when I first picked it up, in a second-hand bookshop in Sutton, was that it provides a different landscape for understanding the emergence of capitalism and empire. The first people colonised were not the Irish, in many ways, they were the British. The imposition of a uniform culture and religion is apparent in Blake’s work, the loss of diversity in defining a ‘good’ or ‘meaningful’ life is replete in the rallying cries of Milton against Newton and Locke and Rousseau.

Reading Milton today, I read it as an obituary to magic, an obituary to a world that imbued the everyday with the spiritual, or rather that saw the spiritual as everyday. And I find it a lot more relevant, a lot more poignant than I did twenty years ago. So perhaps, despite his centrality to Britishness and, perhaps the ultimate irony, Church of England Christianity, I find in Milton today a new way in to understanding decolonisation. And I’m savouring it.

Along with my children’s joy in the word Golganooza.