I’ve been listening to the Philosophy For Our Times podcast, and working through the back catalogue, and its making me dwell on the idea of truth. As a journalist, and as a scholar, the idea of a single truth has been one I’ve grappled with for a while.

As a naive 14-year-old, it was something I hankered after. Malaysia was under the thumb of Ops Lalang, which included a crack-down on the media. The truth was being hidden from us, if we only had independent, free or underground media, then the truth, singular and transcendent, would be apparent and people would recognise it, in an almost Cartesian moment of clarity, and they would work together to build a more democratic and somehow better world.

By the time I was studying political sociology at Oxford, my views on democracy and truth were both more jaded. I had been at a notorious Anti-Nazi League rally in London, and been confounded that the free media of London, with the bizarre but noticeable exception of the music press, failed to report what I had seen happen, hadn’t even attempted to find a semblance of truth. Yet – despite studying philosophy, despite living politics – I still clung for at least a decade more to the idea that somewhere, out there, lived the truth, and that I would recognise it when I saw it.

Slowly, I edged away from this perspective. I found myself increasingly frustrated by the journalistic insistence on two sides to a story, when the majority of stories I found myself working on had more sides than a Dungeons and Dragons dice. And that laid the foundation for wondering, where truth ‘really’ lay in these stories, and increasingly I began to realise that truth was a bit like a perfect map.

The perfect map, of course (and I realise I should cite someone here, but I’m not sure who, Kafka?) is exactly as big as the thing it maps. If it is an iota smaller, it loses some small detail that detracts from its perfection. The truth of the matter, likewise, is the thing itself – no retelling, no recreation can be perfect, because somewhere along the way a detail is lost, a perspective given over-prominence, something is forgotten.

During my far-more-recent post-graduate years, though, I found myself struggling with how to define this. In a room full of much younger, far more intelligent, post-graduates, I was disconcerted with the ease with which they asserted that truth was what was accepted by the majority. If the majority of people believe, let’s say, that the earth is round, why then, that makes the earth round. Or, if you live in Malaysia, the Holocaust never happened, and if you live in America, democracy is whatever is good for business.

And it made me wonder. If you refuse to accept the truth of the majority, if you assert, against the majority, that the Holocaust happened, let’s say, then you are living an alternate truth. Is that not the definition of madness? Unable to absorb and assert to the truth of the world as it is? But then, it might offer a useful diagnosis of the United States at this point in time, a split personality, warring truths creating dangerous instability.

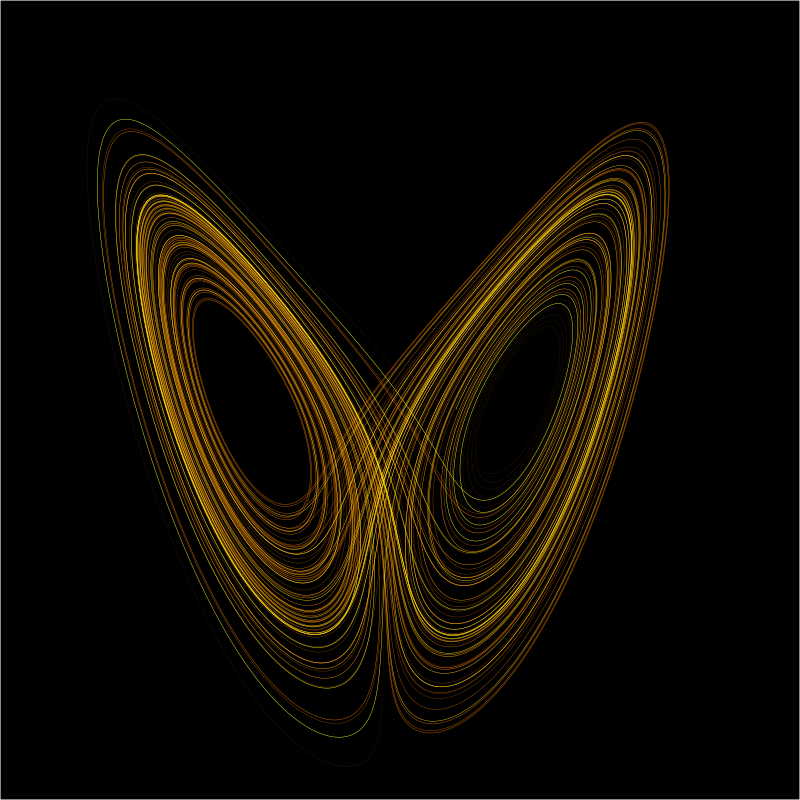

Unfortunately, I want it all. I want to be able to assert that there are multiple truths, but that there is also an objective reality – and that is where I think science offers us a good metaphor. Because it seems to me that chaos theory’s strange attractors give us precisely the image with which to understand our own understanding of the world. There is an objective reality, around which our understandings oscillate. Over time, and given enough repetition, we can discern patterns. And minor perturbations could give rise to huge differences, despite the same underlying attractor or equation.

I can see that there are lots of objections that could be raised against my idea, but it’s my way of trying to understand a complex world. I’d love to hear how you are trying to make sense of these lines and movements, and how your models are better than mine.